Due to open in 2016, the Gotthard base tunnel is not just a hole through a mountain. For ten years hundreds of workers braved tropical temperatures underground and the threat of water in the rock to build the longest railway tunnel in the world.

Travelling at 250 km/h you will hardly notice them, and if all goes well, they will never be used by railway passengers: Yet the emergency exits in the 57-kilometre tunnel are a little marvel of engineering.

“We had to design doors that can be opened by a child and that at the same time will stop the spread of fire and smoke. They have to work even if there is no electricity, and stand up to the wave of pressure, equal to ten tons, caused by trains going by,” explains Peter Schuster of the engineering firm Ernst Basler+Partner.

Situated every 325 metres, the green sliding doors to the escape routes are the result of careful design. It took five prototypes before they arrived at this kind of structure “ugly to look at and very expensive”, but uniquely suitable. “Even the smallest things tested the creativity of the engineers,” notes Schuster, who together with other specialists presented his work at an information day organised by the Swiss Association of Consulting Engineers in early September.

Safety was priority

One of the first challenges faced by the engineers of the AlpTransit project was to map out a pathway for the tunnel that would be entirely level. But it wasn’t enough just to draw a line between the two portals, points out Fabiana Henke of Ernst Basler+Partner.

“We had to consider various aspects: geological conditions, geographical criteria like the height of the rock covering overhead, which can be up to 2,300 metres thick, and the need to build access tunnels to the work sites.”

They also had to be concerned about dams, something that might not seem to have much to do with an underground tunnel. “We had to avoid the reservoirs on the Gotthard, to limit any chance of water seeping in,” says Henke.

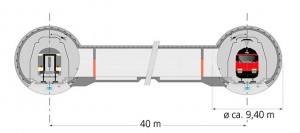

The question then arose of what kind of system to use – a two-way tunnel with another service tunnel, like the Gotthard road tunnel, or three parallel tunnels like in the Channel tunnel? The final choice was a compromise: two one-way tunnels. “It was for safety reasons, most of all, but also because of maintenance, and of course the cost,” says Schuster.

Umbrella in a tunnel

At the time of the first blasting done in 1999, no one could foretell the conditions that would be found deep inside the mountain. It was known that the high temperatures would not make the work of the miners and engineers easy.

Inside the tunnel they measured a high of 45°C, far above the safety limit of 28°C laid down by the Swiss workplace accident insurer.

“We had to build refrigerated areas and ventilation equipment for the workers,” recalls Schuster. Once the tunnel starts operating, the temperature will be able to be kept down using the cooler air carried into the tunnel by the trains passing through.

Another challenge was the presence of water in the rock. One of the trickiest sections was the notorious Piora syncline, an area rich in dolomite where geologists feared they might encounter an expanse of rock filled with water and under high pressure.

This scenario would have spelled the end of the entire project. To the relief of all involved, tests showed that lower down, at the level where the tunnel was going through, the rock was quite dry.

To make the tunnel completely watertight, the engineers decided on an “umbrella” approach, as Henke explains. The vault of the tunnel was covered with a layer of concrete and a waterproof mantle, which allows the water to flow down inside the walls and be channelled out through pipes placed under the railway tracks.

Challenge of a long-term project

“You might say that a tunnel is always a tunnel, whatever its length, and so the final product is always the same,” says Davide Merlini, head of underground works at Pini Swiss Engineers.

But for a tunnel as long as the Gotthard, he points out, the logistical effort needs to be at a much higher level and represents “a project within the project”. In the most intense phase of excavation, about 700 people were working in the tunnel all at once.

One factor complicating things, he goes on, was the sheer length of the project in terms of time. “From the time planning started to when the tunnel was built it took over ten years.” This was a stretch of time in which many things could change, including the technology used.

Some elements already installed had to be replaced before operations began in order to meet increasingly more sophisticated technical requirements, notes Roger Wiederkehr, an engineer with the Pöyry Group who was responsible for the traction current lines in the tunnel.

In the space of a decade, even some of the relevant standards and legislation changed. For example, legislation is now in place requiring a section break in the traction current lines every five kilometres. “It was a safety issue – in case of fire, the whole power line is not damaged, and the train ahead or behind can keep on moving,” explains Wiederkehr.

A model for export

As they wait for June 2, 2016, the target date for the inauguration of the tunnel, the engineers have already “exported” some of the skills they learned in the Gotthard. For example, the Brenner base tunnel between Austria and Italy has now adopted the same double tube system. “Another of the objectives of these major projects is to sell Swiss engineering abroad,” adds Merlini.

The engineers and the mineworkers who built the new Gotthard tunnel are very aware of having achieved a construction feat without precedent.

According to Merlini, “every project has its own beauty, its complexity, and I have the greatest respect for all of them. But for sure, having achieved a gigantic job like this lets us tackle other projects with greater assurance.”

12 billion franc tunnel

The Gotthard base tunnel is 57 km long. The tunnel between Erstfeld and Bodio, linking central with southern Switzerland, is the longest railway tunnel in the world.

About 2,600 people were involved in this construction project. 80% of the excavation work was done by boring machines and 20% by blasting. The cost of the whole operation was CHF12.4 billion ($13.2 billion).

When the tunnel is opened in June 2016, passenger trains will be able to reach a maximum speed of 250km/h (160m/h for goods trains).

When the other major effort of the AlpTransit project, the tunnel under Monte Ceneri, is finished, it will be possible to travel from Zurich to Milan in less than three hours.

Shortage of engineers in Switzerland

“Without engineers, the new transalpine railway would not exist,” says Heinz Marti, president of the Association of Consulting Engineers.

This proud claim is also intended as a warning – in Marti’s view, the profession lacks qualified manpower, and many jobs for engineers are not being filled. The reason is that the engineering profession is not well known among students and the earning prospects do not seem attractive enough compared with the very rigorous period of training.

In an interview with public radio, Marti estimated that about 4,000 jobs come up every year. Of these, 800 have to be filled with engineers from abroad, despite immigration curbs accepted by Swiss voters in February 2014.

A generation of engineers with a lot of experience is now gradually retiring, Marti adds. And even when it is up and running, the Gotthard tunnel will still need engineers.

By Luigi Jorio

(Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee)

Source: Swissinfo.ch